American Chemical Society | Industry | Industry Matters Newsletter | Developing A New Pasta

Developing A New Pasta

Industry Matters Newsletter August 26, 2021

Every product development story starts with an inspiration,

an observation something can be improved, that there is an unmet need.

The story of cascatelli, a new pasta shape begins with recognizing

spaghetti sucks. The surface area of

spaghetti noodles is low relative to the volume of the noodles.

Sauce simply cannot adhere well.

The mouth feel of the noodles suffers.

There isn’t much noodle to resist your bite.

Believing there was a better way powered

Dan Pashman’s quest to develop and commercialize a new pasta shape.

The cascatelli story is a story worth hearing for anyone

doing development and scale-up in chemicals and materials.

Creating a new pasta addresses a market where incumbents exist, as is

most commonly the case with chemicals and materials.

Scale loomed large, as is commonly the case with chemicals and materials. It

is a story documented

in an interesting series of audio podcasts. . The story of

cascatelli describes many of the common challenges and many of the characters

inhabiting many new product development stories.

Dan, the passionate inventor in this story, does a very

smart thing. Before trying to invent

an improvement to spaghetti, he delves into the competitive landscape.

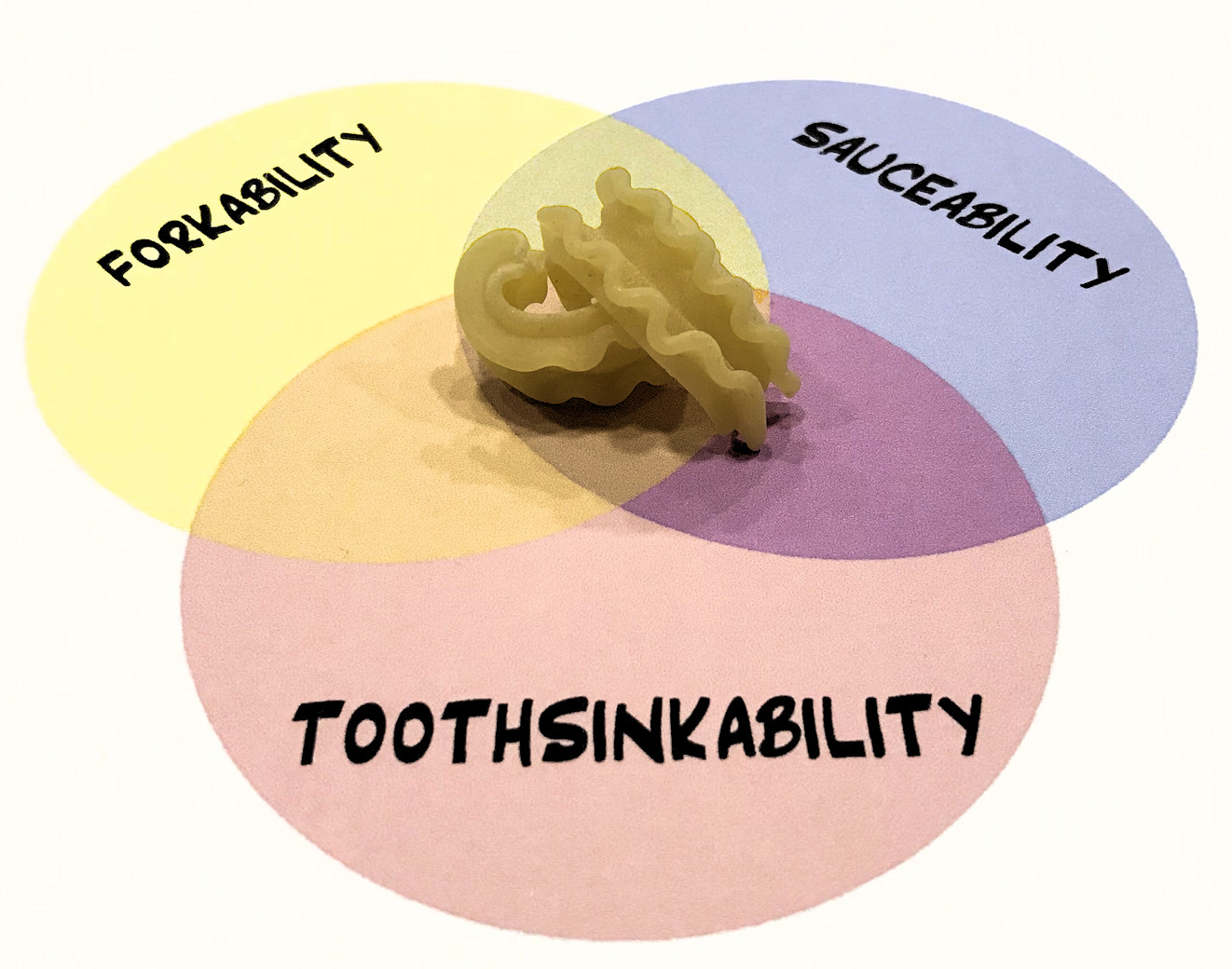

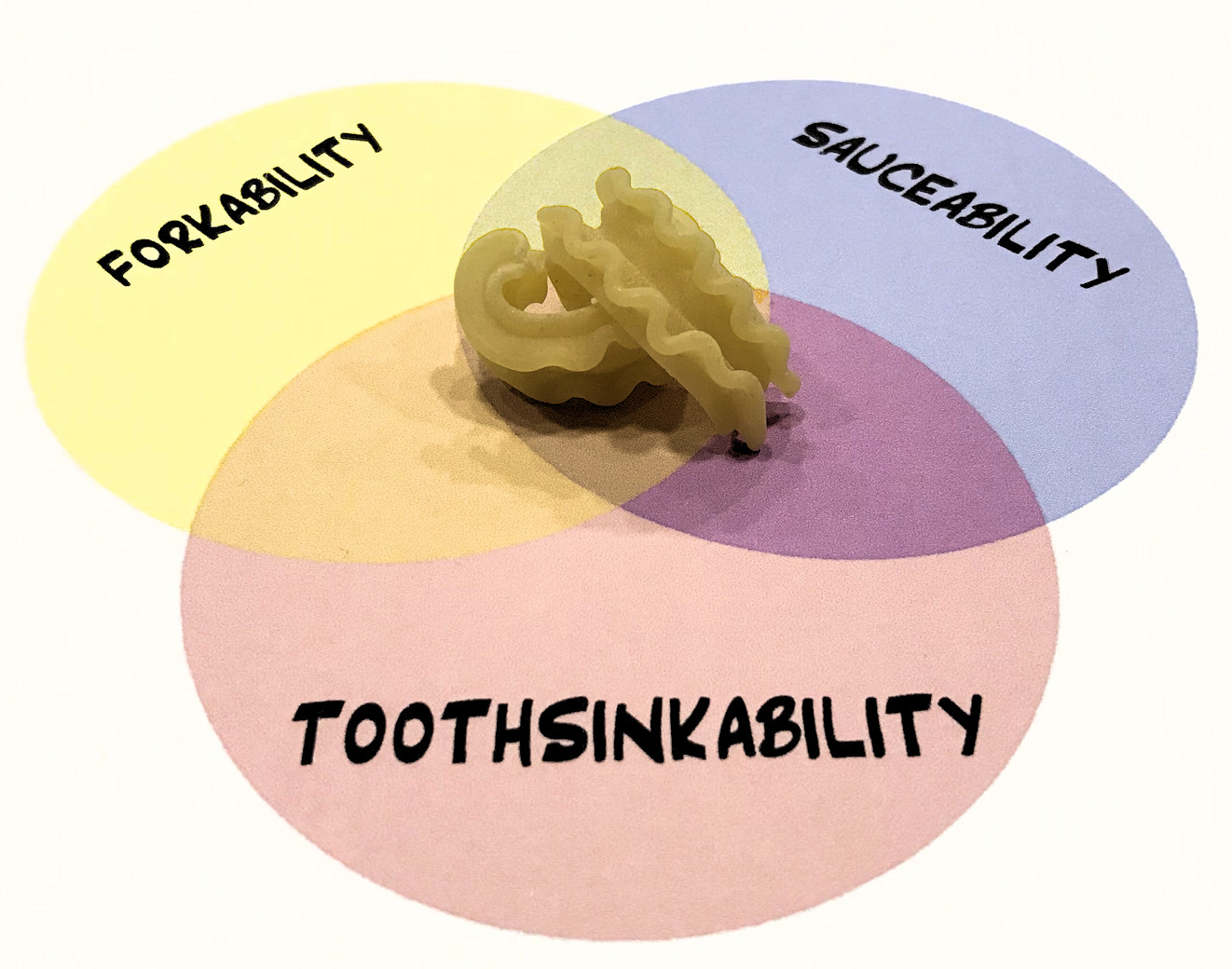

Even smarter, as he evaluates the competition, he develops three

unambiguous metrics to guide comparison.

Forkability, sauceability and toothsinkability form the basis for

assessing the competitive landscape and, ultimately, to guide invention.

Forkability is a measure of the ease of getting the pasta shape onto a

fork and keeping it there.

Sauceability measures how the shape retains sauce.

Measuring how satisfying the pasta is to sink your teeth into is

toothsinkability.

Study of competing pasta shapes convinces Dan he’s onto

something. The reason there are so

many pasta shapes is the incumbent shapes all are deficient when measured

against the metrics. Three clear metrics

enable systematic comparison of existing pasta shapes.

The metrics are also amazingly useful in describing the unmet need in a

clear and unambiguous way, important for recruitment of others to the quest.

Testing the idea with experts is where Dan smartly heads

next. It is during this phase a

common character in product development stories emerges, the nay-sayer.

He approaches experts at the Durum Wheat Quality and Pasta Processing

Laboratory, also known as The Pasta Lab, at North Dakota State University in

Fargo. They question the quest.

Maureen Fant, a pasta historian, said she would not encourage anyone to

invent a new pasta shape. Chris

Maldari, Vice President at D. Maldari & Sons,

one of the largest manufacturers of pasta dies, pulls no punches.

He illuminates challenges in not only coming up with an improved shape,

but also in the cost and complexity of getting it made.

“I can’t tell you that you’re going to get anywhere with this idea” Chris

tells Dan.

Dan, true to the passionate inventor archetype, refuses to

take no for an answer. He finds a

way. The die gets made and, after

some adjustments, is able to make exactly the shape Dan desires, long noodles

with a thicker region at the center delivering forkability and toothsinkability.

Sauce clings to frilly edges to deliver saucability.

Die in hand, Dan now faced the challenge of scale-up.

Early in my career, I was taught this adage about scale-up:

Good, fast or cheap. Pick no

more than two. It is recognition

trade-offs are inevitable. Dan

desired to make a long, flat pasta.

Technical challenges force reconsidering the shape due to economics.

Problems boxing long frilly pasta means large boxes and high cost.

Dan pivots to a short pasta.

He compromises.

Scaling production is part of the story I found

particularly illuminating. I’ve

spent countless hours describing the

impact of scale in chemical

production. The importance of

scale in pasta wasn’t immediately evident to me, but economics and consolidation

drove pasta production to larger and larger scales.

Dan first encountered consolidation with the pasta die.

D. Maldari & Sons joined up with De Mari Pasta Dies, their major

competitor, in 2018. There was only one

choice for die production, thanks to consolidation.

Scale drove consolidation in pasta production.

Pasta seems like something where scale wouldn’t matter,

small local producers should be viable.

Small, regional pasta makers were bought up and shut down as larger and

larger factories gained economies of scale, benefitting from improved production

and supply chain economics. A

typical pasta train is over 85 million pounds per year, 10,000 pounds per hour.

Lines of that scale just can’t economically shift to make the total 5,000

pound run Dan desired. Scale and

consolidation impact other commodity food items.

Bread.

Eggs.

Milk. All are seeing the number

of production facilities decrease even as the overall markets increase.

Exactly the trends seen in chemicals.

Dan’s identification of a compelling need, evaluation of

competing technology, consultation with experts, and willingness to collaborate

is a great roadmap for product development.

The characters who populate his

story are common to many product development stories.

The technical expert curmudgeon that turns into a champion, the technical

enabler, and, of course, the passionate inventor.

He unexpectedly encountered something quite common in the chemical

industry, the challenge of scale. In

overcoming scale-up and other obstacles, the story of cascatelli is one worth

hearing for anyone doing development in chemicals and materials.